If you are a dancer who has trouble finding a “right” beat to start dancing on, or difficulties keeping dancing in time with the music, then you are certainly in the majority of the population, in the majority of beginner dancers, and probably in the majority of all regular social dancers and all dancers who take classes at higher than beginner levels.

I came to this assessment as a teenage musician, and have become increasingly confident about it over the subsequent decades.

For most of my life I thought that there was a complexity in dance timing that was beyond me, as nearly all dancers I watched appeared to move in patterns and to rhythms that had very little relation to what I was hearing or what my bands were playing. The Eureka moment happened for me when our jazz big band played for a Swing Dance ball attended by international, national and local dancers, all of whom danced in time and in keeping with our music throughout the evening. With the great dance timing mystery solved I took the plunge into dance classes myself in a variety of genres and am making up for lost time.

I’ve decided that now is as good a time as any to make a few suggestions to anyone who wants to listen, about how dancers can help themselves to overcome those “when to start” and “staying in time” challenges.

Here goes!

STRUCTURAL ELEMENTS OF DANCE MUSIC

All dance music adopts certain structural elements, some of which are obvious and the rest of which can be learnt. Dance music for Latin and ballroom, salsa, Argentine tango, West Coast swing, rock n’ roll and Ceroc dancing (and presumably most other dance forms) have elements that include:

• a stream of musical notes that have a regular pulse, with the notes typically being written and recognised as being within a continuous series of “bars” or “measures”

• a melody and lyrics (in the cases of songs), which are usually the most recognisable elements of tunes or songs

• a tempo or speed of the rhythm or underlying beat (often expressed as so many beats per minute)

• an even or uneven distribution of consecutively played or sung notes (resulting in the tune or song having a swing feel, or a Latin or other non-swing feel)

• the repetition of verses and choruses throughout the tunes or songs, plus sometimes an introduction, an ending and other sections, such as a bridge or pre-chorus

• layers of sounds coming from the various musicians and their instruments that can be heard as harmonies, chords, accents, etc

There are often other elements, but improving the ability to listen for, recognise and understand a bit more about just those listed above, would be a significant step in improving a dancer’s ability to decide when to start dancing and then how to stay in time.

LANGUAGES TO TALK MUSIC AND DANCE

In the interests of making sure we are speaking the same language, and of enabling you to put into practice some of my suggestions, I need to explain a little about some alternative languages of music, and in particular about bars and notes. If I didn’t, and then I was to suggest how you might go about working out how to find a particular beat of a bar, we could be totally at cross purposes. It’s not necessary for a dancer to have more than a passing familiarity with just one of the various languages, but greater familiarity can certainly aid communication.

I’ll be refering to the tune “Sing Sing Sing” by legendary drummer Gene Krupa, so here’s a YouTube clip of it by the Benny Goodman Big Band (with Gene on drums), if you want to check it out (or have it as background music while you read on):

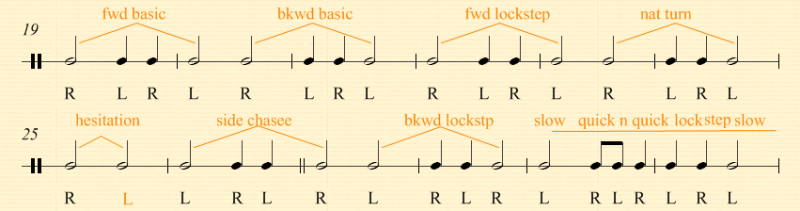

• A musical language that is universally employed by classical and other musicians with formal training is to represent music as notes within bars, using semibreves, minims, crotchets, quavers, rests, ties, etc. Here is an example of how classical music notation could be used to notate dance steps so that they are exactly in time with the music (in this case notating quickstep steps danced to “Sing Sing Sing” for twelve bars from bars 20 to 31 inclusive):

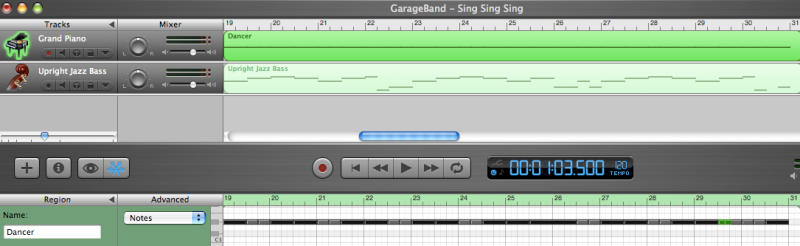

• Another highly visual language, widely used in recording studios is a graphical system to represent notes as bar graphs displayed above or below a time scale that extends for the duration of a song. [Maybe that’s why they’re called bars?] It may or may not be apparent that if the tempo of a piece of recorded music is precisely constant, then the time scale in the bar graph will be able to be delineated as the bar numbers a musician would use to play the music (as an alternative to minutes and seconds). Here is an example of how quickstep dance steps to bars 20 to 30 of “Sing Sing Sing” could be represented so that they are exactly in time with the music:

• Yet another language is the spoken language of dance school instructors who may describe the timing of the steps represented in terms of “Slows” and “Quick Quicks” with the duration of a Slow being exactly twice the duration of every Quick. Using this language each bar of music with four beats to the bar would comprise either two Quicks and one Slow, or two Slows, or four Quicks. A dancer needs to adhere to these durations to stay exactly in time with the music. What I believe that many dancers do not grasp in this language alternative is that once started, the time interval from one Quick to the next Quick or Slow will be exactly the same throughout the music, just like the precise regularity of a slow constant output machine gun with a jammed trigger, or the ticks and tocks of a grandfather clock. Here is a shorthand version of how the above Sing Sing Sing dance steps could be represented.

S QQS S QQS S QQS S QQS S S S QQS S QQS S Q&QQQS

It is worth noting that in the latter of the three languages above, it is less obvious than in the former two that the dance steps are (or should be) just as integrated with the music as every note played by every musician playing the music.

Notes on Playing with Time

It should also be recognised that there are times (actually plenty of times) when musicians (and dancers) can compress or extend the duration of their notes (or steps), and to advance or retard the start or finish of a note (or step). Reasons for this could be to try to create tension, excitement, ambiguity, smoothness, anticipation or some other emotion, and (particularly in jazz) different musicians might deliberately play all of their notes or beats very slightly earlier or later than others in a band in order to create a particular overall sound for a tune. This effect can be readily apparent when a jazz vocalist sings phrases that are noticeably earlier or later than usual, and when a professional dancing couple dancing a slow foxtrot steps later or earlier for at least one step in each bar. In all instances of musicians and dancers “playing with the time” like this, it is invariably obvious to nearly everyone whether they are witnessing imaginative artistry in action or whether they are witnessing a slip up or (worse) an inability to stay in time. The former are always aware of where the fundamental timing lies and (usually) they can move right back on beat any time they want to.

Here’s a YouTube clip of great timing for a slow foxtrot to “straight” (non-swing) music with a nice balance between being right on time and incorporating a little play time:

It should also be recognised that the tempo, timing and feel of music can and often do change during a single piece of music, and that dancers should ideally adapt what they are doing to reflect such changes. This is particularly common in Argentinian tango music with long pauses and sections with little or no underlying pulse before the former tempo resumes or a new tempo commences. While it is less common in other dance music, there are several well known songs with significant variations that dancers would do well to familiarise themselves with, including the jazz classic Night in Tunisia (which is normally played with a Turkish / Latin feel in the main sections but a swing feel in the bridge), the pop song Flashdance (which has an extended slow introduction before changing to a driving tempo), New York New York (which has some tempo changes), and Burt Bacherach’s The Look of Love (which has a two beat extension in one bar of each chorus).

In closing on languages for music and dance, I suggest that what is important to a dancer is to be aware that dance music ticks along at the tempo adopted by the musicians performing it, so to dance in time to it, a dancer must hear the beats and have a system to work out how to match dance steps to music beats being played.

SUGGESTIONS AND EXERCISES FOR DANCING IN TIME

Dance in time by listening to melodies and lyrics

I expect that many dancers and other listeners to music limit their real understanding of a tune or song they hear, to the lyrics and melody, and maintain only a general recognition that there are some other things going on in support, without much attention being given to what these might be.

The good news for these dancers (as well as everyone else) is that melodies and lyrics can be really useful in identifying and helping to get an understanding of nearly all of the other elements.

For example:

• If in the first few seconds before you decide to start dancing, you listen to the tempo at which the initial lyrics of a song are sung, you can have some confidence that this will be the ongoing tempo of the song.

• If you are not aware of a style to dance for a song, there may be some hints in the evenness or bounciness / swing of the singer’s delivery, or even in the language a song is sung; with clear evenness or a Latin lyric language often being indicative of a Latin style of dance.

• Lyrics and melodies are typically phrased to extend to cycles of two or four bars of music, for a variety of musical reasons as well as to enable vocalists (and musicians playing blowing instruments) to get regular spaces in their delivery to inhale new breaths. These phrases can provide a useful road map through a song and enable you to check regularly if your dancing is in synch with the song.

• Similarly the repetition of a melody for a verse and the repetition of a melody and lyrics for the chorus of a song provide great points to make mental reassessments of your dancing and how you are aligning it with the song you are dancing to.

• The accents and other nuances in a singer’s voice can also often provide excellent indications of the whereabouts of the ever-important first beat of a bar of music. In the swing standard “L.O.V.E.” made popular by Nat King Cole, the sung letters L, O, V and E are emphasised on the first beat of the bar throughout most of the song, making it very easy to keep in time. Here is a cover by the cast of Glee:

A little more challenging is the Latin (cha cha) “Sway”. The delivery of the lyrics “When marimba rhythms start to play” and later “Like a flower bending in the breeze”, places the emphasis (as does the entry of the supporting backing music) on “start” and “in” respectively, which reinforces that these mark the first beat of the bar and the first beat of each verse. Incidentally for “Sway” the words “When” and “Like” in the phrases mentioned, are sung on beat two. Here’s a version by the Pussy Cat Dolls:

• A good exercise to build up familiarity with how vocal lines sound that start on different beats in the bar would be to identify a collection of songs that are likely to have different starting beats, write down the lyrics for the first sung phrase, then listen to (the starts of) recordings of all the songs several times in random order, noting which beat you think the vocals start on and which is the first beat of the bar. The songs could be as old or modern and as sophisticated or simple as you like. Any album of your favourite dance music would be good, as would even a collection of Christmas Carols or nursery rhymes; although in both these latter cases I expect you would find that the vocals start mainly on beat one with most of the rest starting on beat four. Here are examples of some Beatles songs that start on different beats:

| First syllable | Song | Next Bar | ||||

| Beat 1 | Beat 2 | Beat 3 | Beat 4 | Beat 1 | ||

| Beat 1 | Lucy in the Sky | Lu -cy | in the | sky | - with | dia(monds) |

| Beat 1 & | Dizzy Miss Lizzy | - You | make me | dizzy | Miss | Liz - zy |

| Beat 2 | Can't Buy Me Love | - | Can't | buy | me | love |

| Beat 2 & | I Saw Her Standing | - | - Well | she was | just | |

| Beat 3 | Twist and Shout | - | - | Shake it | up | baby |

| Beat 3 & | Hard Days's Night | - | - | - It's | been a | hard |

| Beat 4 | Ob-La-De | - | - | - | Ob-La | De |

| Beat 4 & | Sgt Pepper's | - | - | - | - We're | Sergeant |

The more you listen to songs you like and find which words or syllables (or notes within a melody) are on beat one, the better you will get at hearing it for other songs. If you can’t find a beat one syllable or note any time, you can either keep replaying the song till you get it, use one of the other suggested systems, or ask others to help you find it.

Dance in time by listening to rhythms and tempo

For any tune or song, all the musicians have to adopt the same tempos and rhythms for it to sound coherent, and other than in cases where there are intended tempo or rhythm changes, the tempos and rhythms throughout a tune or song are very close to constant.

If a dancer wants to look great, or even OK, then it is absolutely essential that the dancing is in time with the music!

Further, if a dancer wants to dance in time with the music, as distinct from dancing to something else (like timing patterns in the dancer’s head that aren’t aligned with the underlying tempos and rhythms the musicians have created), then the dancer must have or must learn foot-ear coordination (just as a sportsperson must have or must learn hand-eye coordination).

Nearly everyone demonstrates foot-ear coordination during dance classes while a teacher is counting out the beats of a bar or is calling out the “Slows” and “Quick Quicks”, but for many, everything turns to custard when the calling stops and the music is all that is available; and especially music without vocals. Some conceal the problem by using foot-eye coordination if there is someone reliable in sight who can be copied, but the real solution is to hone listening skills, to develop a better understanding of dance music, and to practice keeping in time.

Here are some things that have worked for me, and that I continue to use to try to understand music with unusual metres (such as with five or seven beats to a bar), to transcribe intricate individual instrument parts in band arrangements, and to analyse music with ambiguities:

• The first involves hand-ear co-ordination, as an interim step in the progression from hand-eye towards foot-ear co-ordination. If you are sitting listening to music, make a habit of lightly tapping your fingers as evenly as you can in time with what you are hearing, using four fingers for tunes that have four beats to the bar (such as foxtrots, quicksteps, cha chas, rumbas and salsas), three fingers for waltzes and two fingers for sambas. What you want to achieve is to make your tapping pattern exactly in time with the music you hear, and for finger one (of the two, three or four fingers used) to always land on the first beat of the bar, so that when the subsequent verses or choruses begin, it will be your finger one that always coincides with each starting beat. [It is best to do your tapping as silently as possible and preferably in total silence to avoid abuse or even physical injury from third parties!]

• If you are listening to music while walking, (or singing, humming or thinking your way through a tune or song while walking) make a habit of walking in time with what you are hearing. What you want to achieve is to walk exactly in time with the music you hear, and (except in the case of waltzes) for the foot you step on for the first beat of a bar to always be the one that lands on the first beat of every other bar, so that when the subsequent verses or choruses begin, it will be the same foot that always coincides with their starting beat. [To do this one it is advisable to select music that doesn’t have a crazily inappropriate tempo for walking!]

• If you are sitting watching dancers at a dance, use the finger exercise for the music being danced to, and check out which dancers are keeping to the timing you are tapping out. It is most likely they will be the better ones; provided (of course) your tapping is accurate.

Some genres of music tend to have a very clear beat and an obvious beat one (including most foxtrots, waltzes, sambas, tangos and cha chas) but others (including salsas, jives, rumbas and other tunes performed in an improvised jazz style) can be very difficult for reasons of their high-speed tempos, their pauses or the syncopation incorporated in the music. For these more challenging cases, the systems suggested do work, but there may also need to be more time spent developing a better understanding of what you are hearing.

Challenges of Latin Music for Dancers

In my experience, it is Latin mambo and salsa music that dancers find most challenging, so here are a few insights that will hopefully be useful (or at least insightful):

• Traditionally, Latin music has had more than one percussionist, generating strong and busy rhythmic drumming, with patterns of strong accents and normally very steady timing. Typically the percussion is phrased in pairs of two bars; each pair providing a “clave” of three strong beats in one bar and two in the other, with beat one of the two-strong-beat bar being silent or having sounds continuing to ring from the fourth beat of the previous bar. The clave can be either 3-2 or 2-3, reflecting the order of the two bars, which are invariably unchanged throughout.

For example in a Brazilian Bossanova like “Girl From Ipanema” the rhythm is usually counted as |1 (2)& (3) 4 | (1) 2 (3)& (4) | making it a 3-2 clave. Have a listen to this 16 bar audio clip from Girl From Ipanema:

You should be able to hear accented drum beats playing the bolded beats. You may as well check out your tapping skills while you’re at it; tapping the four beats in each bar and not the clave (unless you want to go to the challenging extreme of tapping the single beats with four fingers of one hand, and the clave accents with three or five fingers of the other hand)!

For a standard rumba to this song, a dancer would start with a rock step on beat one of bar one, then step on beats 2, 3 and 4 of every bar, the result being that (apart from the first rock step) a step would coincide with only the beat 4 accent in one bar and with only the beat 2 accent in the next bar. Dancers who listen out for these accented beats can get confirmation that their timing is spot on (or not) and those who step precisely on those beats will look far better than those who don’t.

• A salsa or mambo dance to a Cuban rhythm can be even more challenging because typical Cuban accented claves often have only an implied beat one leaving the accented clave sounding in some cases |(1) (2)& (3) 4 |(1) 2 (3) (4)& |.

Also in traditional music from Cuba and many other South American countries, the bass (or a percussion substitute) often plays only the “& of 2” and beat 4 in most bars, which can be most off-putting for dancers more attuned to hearing a strong bass beat on beat one.

Here is a short audio clip by leading Latin bassist Oscar Stagnaro playing this bass pattern on the “& of 2” and the fourth beat.

Until I got myself attuned to hearing the strong beat 4 (in particular), I relied primarily on the melodies and lyrics systems described earlier to hear my way through a dance. I also spent a lot of time listening to (and playing) Latin music, tapping out my tempo tapping exercise, watching good salsa dancers in action and taking salsa dance classes.

A Note on Swing and Straight Rhythms

Another useful distinction can be made between swing and straight music (the latter of which includes Latin music).

A song with a “swing” feel is one that has streams of consistently uneven notes that generate a bouncy rhythm characteristic of the swing bands from the 1920s onwards, and of the jive and rock n’ roll music that grew from it. The style drew on the American blues songs brought to and developed in America by African slaves and their descendents, and was a radical contrast in its day to earlier European classical music.

The swing feel is generated by musicians subdividing each beat in a bar of music into uneven “halves”, with the first “half” being anything from a tiny bit bigger than the second, through to being twice as big as the second; equating to “light swing” for the former and “heavy swing” for the latter. It is also normal for the second and fourth beat of each bar to be accented very slightly relative to the first and third beats.

While not directly relevant to working out dance tempos and appropriate starting points, it should be noted that foxtrots, quicksteps, jives and the dances that are direct relatives of these are normally danced to swing music, whereas there are rarely any swung notes in Latin music, although sambas can be interpreted as being totally consistent with a swing rhythm.

Dance in time by listening to verse and chorus structures and repetition

The structures of a tune or song are very helpful in assisting a dancer to work out when to start (and stop) dancing. Each start of a section (and especially a new verse or chorus) can also be used by a dancer to reassess whether they are in time and on their preferred foot for their intended coming choreography.

It is useful to know that there are only a small number of structures and structure lengths incorporated in most tunes and songs.

The three that would account for at least eighty percent of all dance tunes and songs are:

• A 12 bar blues structure – This is a structure often built around three chords that resolves every 12 bars and repeats throughout a tune or song. Examples include most rock n’ roll songs, and most songs by Elvis Presley and the Rolling Stones (to name a just a few).

• An AABA structure – This typically comprises a 16 bar “A” section, which is repeated once, substituted with a contrasting 16 bar “B” section, before the “A” section is played a final time to complete the cycle; all of which can be repeated one or more times. A large number of the songs from the “American Song Book”, including those sung by Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole and now-a-days by Michael Bublé, are examples.

• A pop song structure – This verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, chorus, chorus structure is typical of many pop songs over the last fifty years, with each section often comprising 16 bars.

Variations to the latter two structures are for there to also be an intro, an ending (or coda) and sometimes a pre-chorus.

For dancers, it is useful to develop a sense of what combinations of dance moves equate to exactly four, eight and sixteen bars of music, so that they can be used to match the lengths of the music being danced to, and also maybe varied to provide contrast for different sections. It is worth pointing out that it can be particularly challenging (and rewarding) to gain a sense of what dance moves fit within a 16 or 32 bar structure when the dance styles are based on basics that involve six beats (i.e. a bar and a half), such as a rhythm foxtrot, quickstep, rock n’ roll, jive and West Coast swing. For example, a one and a half bar dance phrase of Slow-Quick-Quick-Slow repeated eight times matches perfectly with a 12 bar music structure, but a variation in the pattern is essential to fit in with 16 bar music structures if a dancer wants to be dancing Slow-Quick-Quick-Slow again at bar 17 or 33 for the first bar and a half of the next 16 bar verse or chorus.

If a dancer can start and end a series of moves to align with the start and end of every verse and chorus of music, then that dancer is almost certainly dancing in time with the music.

A great benefit of the consistency with which the verses and choruses of tunes and songs are structured as 12 of 16 bars, is that a musician or dancer does not have to actually count bars through the music to keep track of when a current verse or chorus is about to end. Rather, the approaching conclusion of a verse or chorus is almost always signalled audibly in the forms of the phrasing of a vocalist’s lyrics, the resolution of the lead melody, extra drumming fills and “turnaround” chord changes by the musicians. By switching from counting to listening mode when a dancer is trying to remember a choreograhed routine (away from a studio), it is easy to think through all the dance steps while simultaneously humming through an appropriate verse or chorus of a song, and checking that the completion of the sequence concludes in the same place on each take; and preferably to coincide with the start of the next section of music.

Dance in time by listening to instrumentation, harmonies and chords

The final elements that I suggest you consider using to assist with timing and with finding an appropriate beat on which to start dancing, are the blocks of sound that are generated by multiple instruments and vocalists to produce harmonies and chords.

While it is possible to dance perfectly in time by listening to only the principal melody of a tune or song together with the sounds of a bass and drums (or a piano or rhythm guitar substituting for one or both of them), there are some really useful signals available from the other voices and instruments being played.

For example, without too much effort, it is quite easy to hear chord changes as they occur in most tunes and songs. Considering the song “Sway”, previously discussed, I have highlighted in the lyrics below, the syllables at which chords can be heard to change, and have added underlines of the words or syllables that coincide with beat one of each four bars (through the song’s first AABA pattern). Like a huge number of other songs the chord changes for Sway occur on the first beat of every two bar phrase, so if a dance leader’s right foot rock step (and the follower’s left foot rock step) lands to match every second chord change in a cha cha danced to this song, the dancers will know that they’re dancing in time, and that they started when they should have.

First A section

When marimba rhythms start to play

Dance with me, make me sway

Like a lazy ocean hugs the shore

Hold me close, sway me more

Second A section

Like a flower bending in the breeze

Bend with me, sway with ease

When we dance you have a way with me

Stay with me, sway with me

B section

Other dancers may be on the floor

Dear, but my eyes will see only you

Only you have that magic technique

When we sway I go weak

Final A section

I can hear the sounds of violins

Long before it begins

Make me thrill as only you know how

Sway me smooth, sway me now

Enough’s enough about dancing in time

I could go on, but expect that if you have read through most of the suggestions I have outlined and implemented even one of the exercises diligently, you will already be better than you were before at finding a correct beat to start dancing on, and better at dancing in time.

Summarising the key suggestions and suggested exercises:

- listen out for, and try to recognise and understand a bit more about the key elements of songs and tunes

- remember that most dance music ticks along at exactly the same tempo throughout and that to dance in time you must adopt the same tempo as the musicians are playing

- listen out for whether music is being performed with a swing or even rhythm before deciding on a style to dance to it

- listen for and try to lock into the tempo of a song for a few seconds before you start dancing

- listen out for the two or four bar phrases and chord changes that are recognisable in most songs and try to relate your dancing to those phrases in length and in other respects

- listen out for the upcoming starts to new verses and choruses and try to align the start of a new sequence of dance moves with them

- spend some time listening to songs for which the lyrics and melody start on different beats of a bar with a view to increasing your ability to identify the first beat of a bar in similarly phrased songs

- practice hand-ear coordination with finger-tapping exercises while listening to music and check your timing by trying to always land the same finger on the first beat of a bar

- practice foot-ear coordination by walking in time with actual or imagined music and check your timing by trying to always land the same foot on the first beat of a bar (unless the tune is a waltz)

- watch other dancers and work though the finger tapping exercises while listening to the music they are dancing to and you are listening to

- spend a lot of time listening to Latin music and try to gradually improve your ability to hear and understand the claves and the beats that good dancers try to always step on

- spend some quiet time and some practice time developing a sense of dance move combinations that equate to exactly four, eight and sixteen bars of music then rehearse new choreography in your mind while humming or thinking through favourite songs of known numbers of bars (rather than counting) being careful to always complete the same sets of moves at the same point in a song

If you want additional suggestions or want me to clarify or expand on anything, please feel free to track me down.

Cheers

Stu

Footnote from Stu:

As a musician in various stages of learning to dance, it is apparent to me that a very large proportion of dancers (including many of my fellow students) have difficulties in either hearing rhythms and tempos, or understanding some fundamental concepts in music that, if heard or understood better, could really benefit their dancing skills and their enjoyment of dancing.

While there are plenty of terrific articles and books on music and musicality for dancers, the ones that I have read seem to be either really basic, or written mainly for experienced dancers, teachers of dance and choreographers, and to be difficult for dancers working to rise above beginner levels (and especially non-musicians) to understand or to apply.

I hope this partly fills the void.